How a one-off romantic story became a historical fiction trilogy spanning three centuries

August has been an incredibly busy month for me. The final manuscript for A Motif of Seasons has been sent for production, and the publicity machine is preparing for action. This has given me time to reflect on my journey as an author over the last few years.

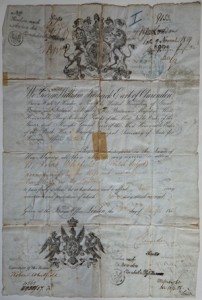

I originally intended for The Music Book to be a one-off historical romance story written for fun. Covering the years 1764–1766 it would be woven around fictional characters in England and Prussia, sparked by an 18th-century portrait of Frederick the Great and a 19th-century British passport in our family’s possession. I did it as a welcome antidote to decades of writing Foreign Office policy papers, briefs and speeches, writing for my own enjoyment and then to share the outcome with others if they so wished.

Once written I felt the characters nagging me to continue the story. Buoyed by some excellent reviews and feedback, I decided to do so in the sequel, Fortune’s Sonata, which covers the much longer period 1767–1816 and is set against the backdrop of the later years of Frederick the Great, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars.

It seemed only fitting to then conclude the chronicle of the two families I introduced in The Music Book, following them from 1853 to the First World War in the final novel A Motif of Seasons.

Though I had access to many sources, the stories stem entirely from my imagination. After dark, during the long winter nights in Norfolk, I was able to shut out the modern world and imagine these families struggling with the bitter legacy of an ancestral marriage in 1766 against a background of looming war. Writing was like driving a car alone late at night across an inky black landscape absent of landmarks – with the way ahead illuminated only a short distance by the two shafts of light from the headlights. Everything else either side or beyond was in darkness, providing ample scope for invention of what might be there. The Herzberg Trilogy is the result of that long dark journey.